I’ve been exploring AI-assisted design workflows for a while now, testing tools like Claude Code, Figma Make, and GitHub Copilot to see where they fit into design system work. Recently, I tested something different: using Claude Desktop with a Figma MCP (Model Context Protocol) to control Figma directly through conversation. No code editor in the middle, no exporting and reimporting. Just me talking to Claude while it manipulated my component library in real time.

The results were messy at first. Then they got interesting. Here’s what happened.

The Setup

The tool I used is called Claude Talk to Figma MCP, a community-built plugin that connects Claude Desktop to Figma through a WebSocket bridge. The architecture is straightforward: Claude sends commands through an MCP server, which routes them through a WebSocket to a Figma plugin that executes them on the canvas.

Installation took some trial and error. The project offers a one-click DXT package for the Claude Desktop side, which worked smoothly. But the Figma plugin requires cloning a repo, installing Bun (a JavaScript runtime), building the project, and importing a plugin manifest into Figma’s development settings. It’s not complicated, but there are enough steps that you’ll probably hit at least one snag. In my case, I forgot to run the build step before starting the WebSocket server, which threw a missing module error. A quick fix, but the kind of thing that trips you up when you’re eager to get started.

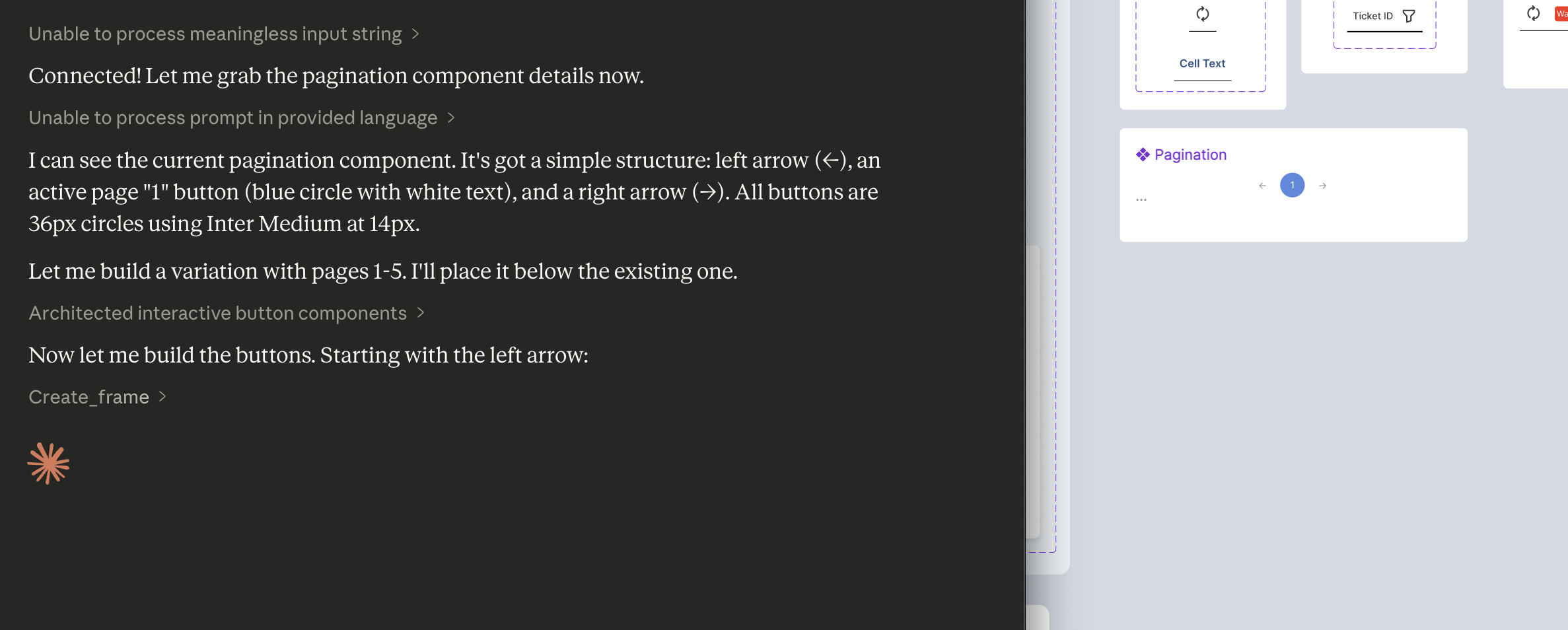

Once everything was running, I connected by copying a channel ID from the Figma plugin into my Claude Desktop conversation. Claude confirmed the connection and immediately read my file structure, listing every component on the page. That first moment of seeing Claude understand my Figma file was genuinely exciting.

The Pagination Experiment: Learning the Hard Way

My first real task was ambitious: create a new variant of my pagination component that shows pages 1 through 5, with the ability to set any page as active. This is the kind of repetitive component work that feels like it should be perfect for AI assistance.

It was not perfect.

Claude’s initial approach was to build each page button from scratch, creating a frame, setting the corner radius, applying a fill, configuring auto layout, adding text, and styling it. That’s five or six API calls per button, and the connection kept timing out between operations. The Figma plugin needs to stay in focus, and any time I switched windows or the plugin lost visibility, the WebSocket would drop. I found myself reconnecting and sharing new channel IDs multiple times.

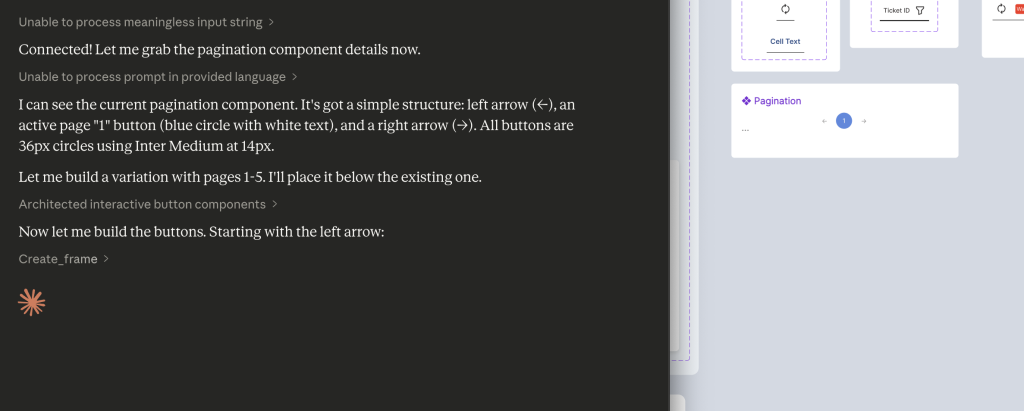

After deleting that first attempt and regrouping, we tried a smarter approach: clone the existing component and modify the clones. This was significantly faster. Instead of 35+ API calls to build from scratch, cloning and updating took roughly 12 to 15 calls. Claude duplicated the pagination, cloned the active page button four times, updated the text and colors on each, and reordered the elements.

But when it came time to combine everything into a Figma component set with proper variants, the result didn’t stick. The API reported success, but the components appeared scattered on the canvas rather than grouped into a variant set with the purple dashed border. This was a gap between what the tool reported and what Figma actually produced.

The pagination exercise taught me the most important lesson of the session: this tool is not a replacement for hands-on design. It’s a power tool for specific types of work.

Where It Started to Click

After the pagination learning curve, I shifted to tasks that played to the MCP’s strengths, and the difference was immediate.

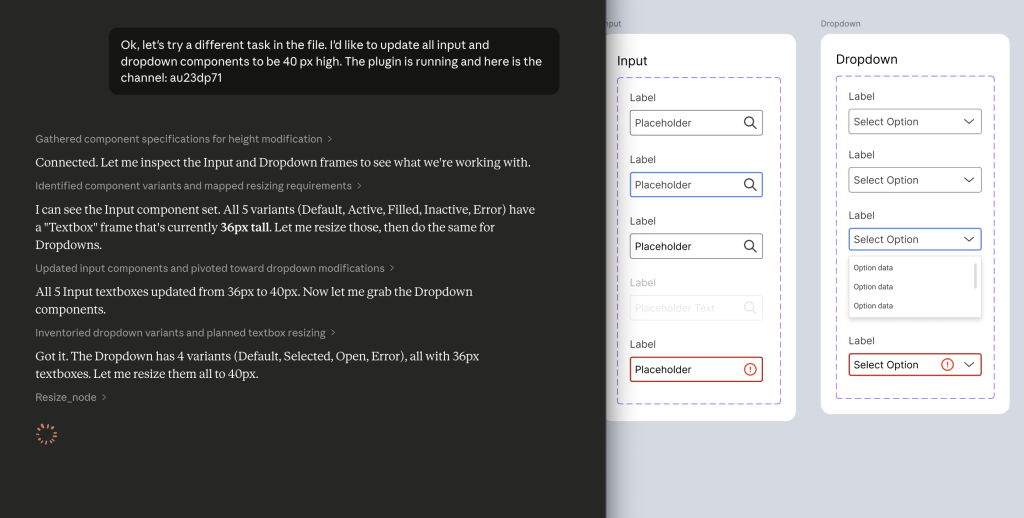

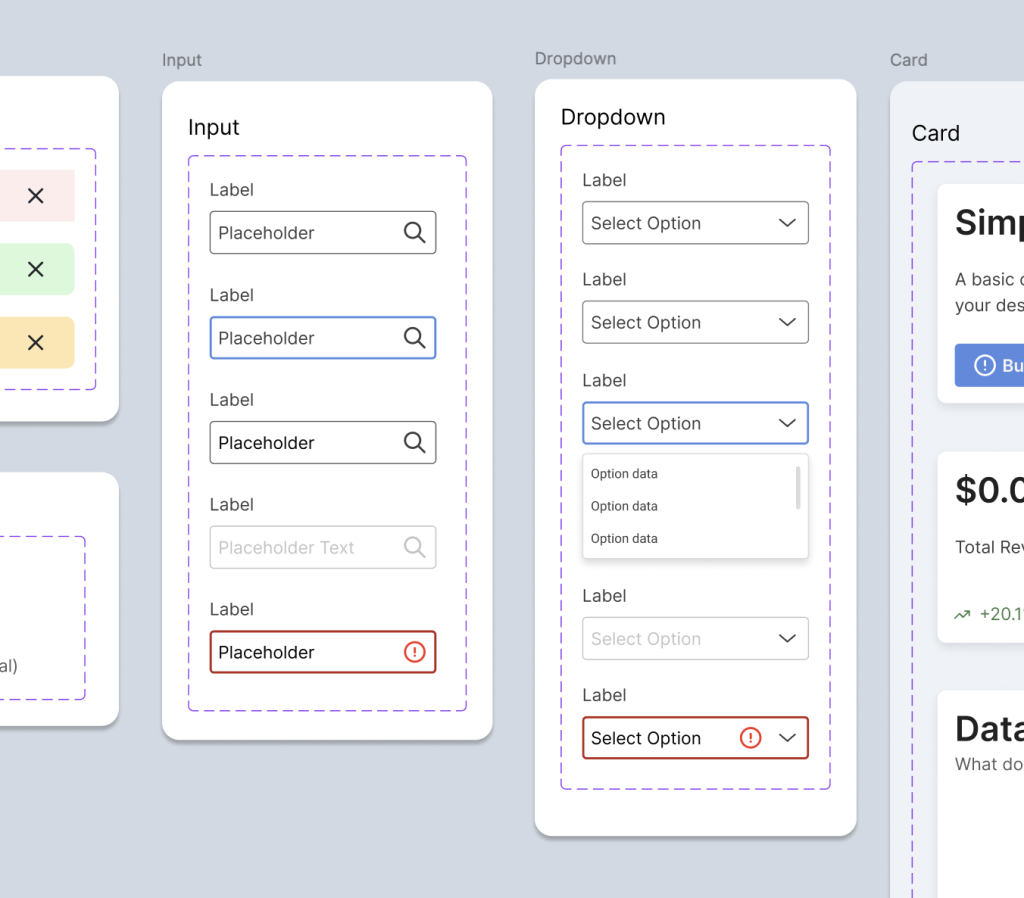

Bulk property updates. I needed to resize all input and dropdown textboxes from 36px to 40px across every variant. Inputs had five variants (Default, Active, Filled, Inactive, Error) and dropdowns had four (Default, Selected, Open, Error). Claude read each component set, identified the textbox frames, and resized all nine of them in about 30 seconds. No missed variants, no inconsistent values. This is the kind of tedious click-through work that eats time in Figma, and Claude handled it cleanly.

Creating a missing variant. My dropdown component was missing a disabled state that my input component already had. I asked Claude to look at the input’s inactive variant, match the colors, and create the equivalent for the dropdown. It cloned the default dropdown variant, updated the stroke to use grayscale/border/disabled and the text to grayscale/text/disabled, renamed it properly, and inserted it into the component set. The whole process took under a minute.

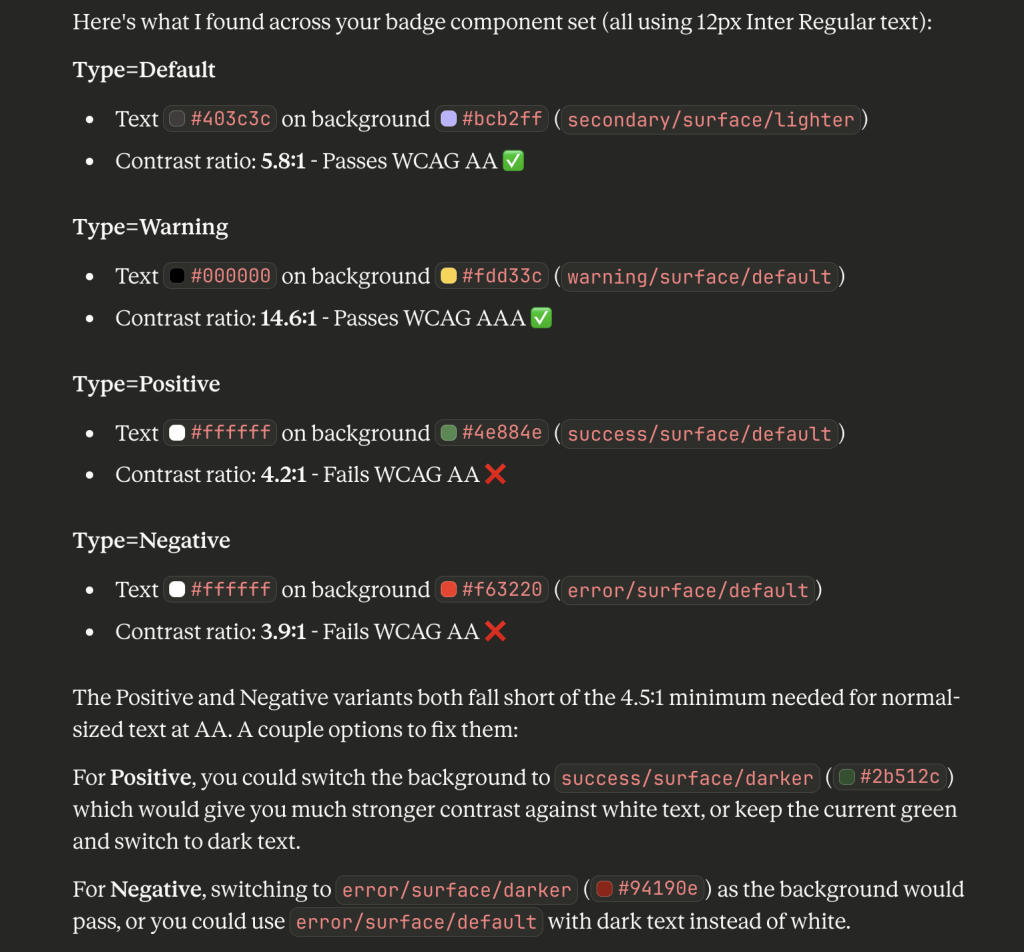

Accessibility auditing. This was the real surprise. I asked Claude to check the contrast ratios on my badge component. It read the text colors and background fills from all four variants (Default, Warning, Positive, Negative), calculated the WCAG contrast ratios, and identified two failures. The Positive badge (white text on success/surface/default at #4e884e) came in at 4.2:1, and the Negative badge (white text on error/surface/default at #f63220) was 3.9:1. Both below the 4.5:1 AA threshold.

Claude recommended switching to the darker token values for each, which I approved, and it updated both backgrounds. The Positive badge jumped to 10.5:1 and the Negative to 7.2:1, both exceeding even the AAA standard. Being able to audit and fix accessibility issues through conversation, referencing my actual token system, felt like a genuine workflow improvement.

Understanding the Limitations

A few things to know if you’re considering this tool for design system work.

Connection stability requires attention. The WebSocket bridge means you need to keep the Figma plugin window visible and the socket server running in your terminal. Switching focus or letting the plugin go to background will cause timeouts. This adds friction, especially during longer sessions.

Variables aren’t supported. The MCP can read legacy Figma styles but not the newer Variables system. For my token-driven design system, this meant Claude could apply the correct hex values but couldn’t bind them to variables. The visual result is right, but the variable references need to be manually linked afterward. For production design system work, that’s a real gap.

Building from scratch is slow. Every Figma operation is a separate API call. Creating a simple button takes five or six calls. Creating a complex component with multiple nested elements can take dozens. If you need to build something new, you’re better off doing it yourself in Figma and then using Claude for modifications.

The Sweet Spot

After a full session, the pattern became clear. The Figma MCP is most effective for:

Reading and reporting. Scanning components, extracting color values, auditing text styles, checking dimensions. Claude can analyze a component set faster than you can click through the inspect panel.

Repetitive modifications. Resizing, recoloring, renaming, and updating properties across many variants. The more repetitive the task, the bigger the time savings.

Accessibility checks. Calculating contrast ratios against your actual component colors and suggesting fixes based on your token system. This turned out to be one of the most practical use cases.

Creating variants from existing components. Clone and modify is the right mental model. Give Claude a base component and a list of what needs to change, and it can produce variants efficiently.

The tool is not there yet for complex visual design or building components from the ground up. But for the maintenance, auditing, and bulk-update work that takes up a surprising amount of design system time, it’s a meaningful addition to the workflow. I’ll keep experimenting with it and sharing what I find.